What Survives When the Engraving Fades? On Mozafar Ramadan’s Temporary Series

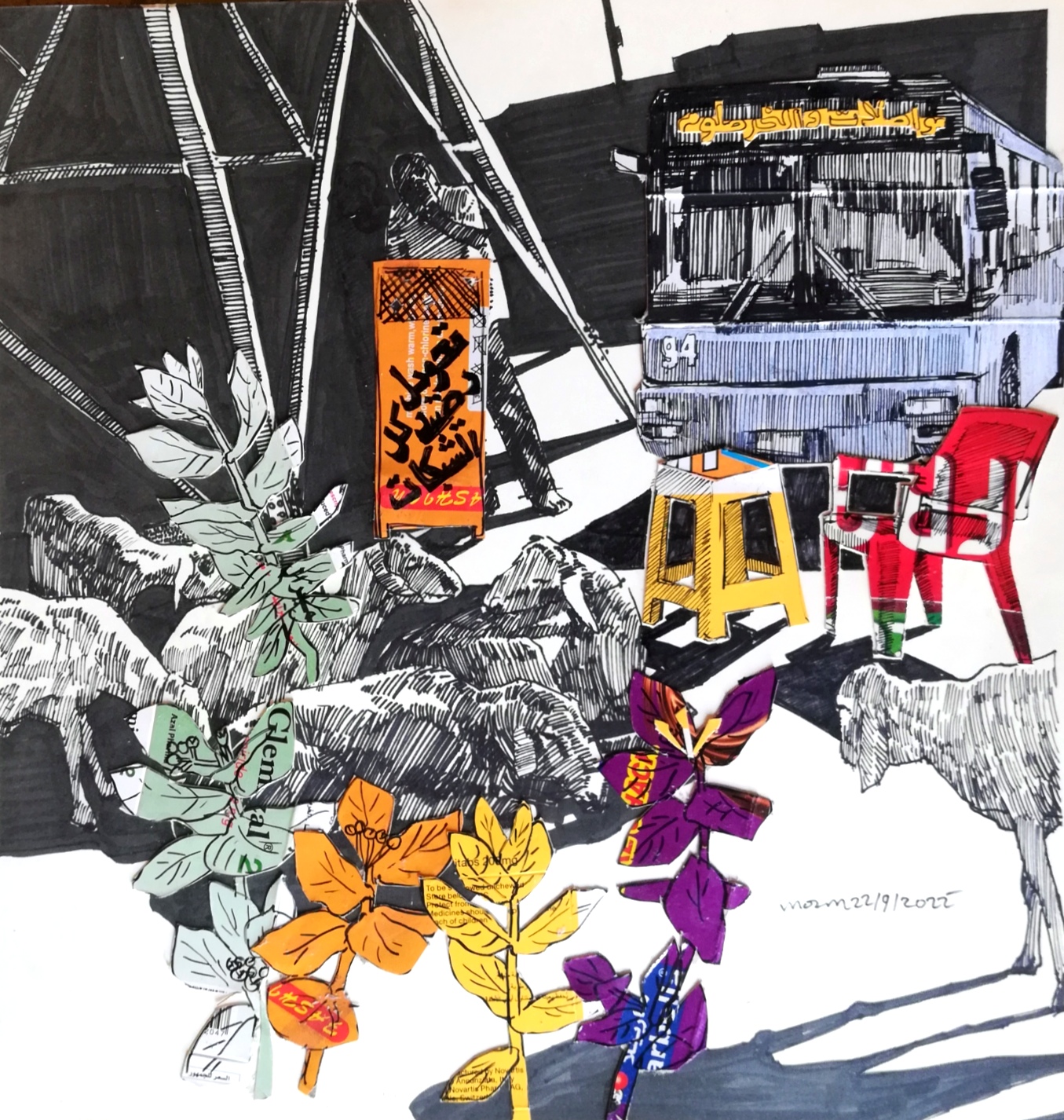

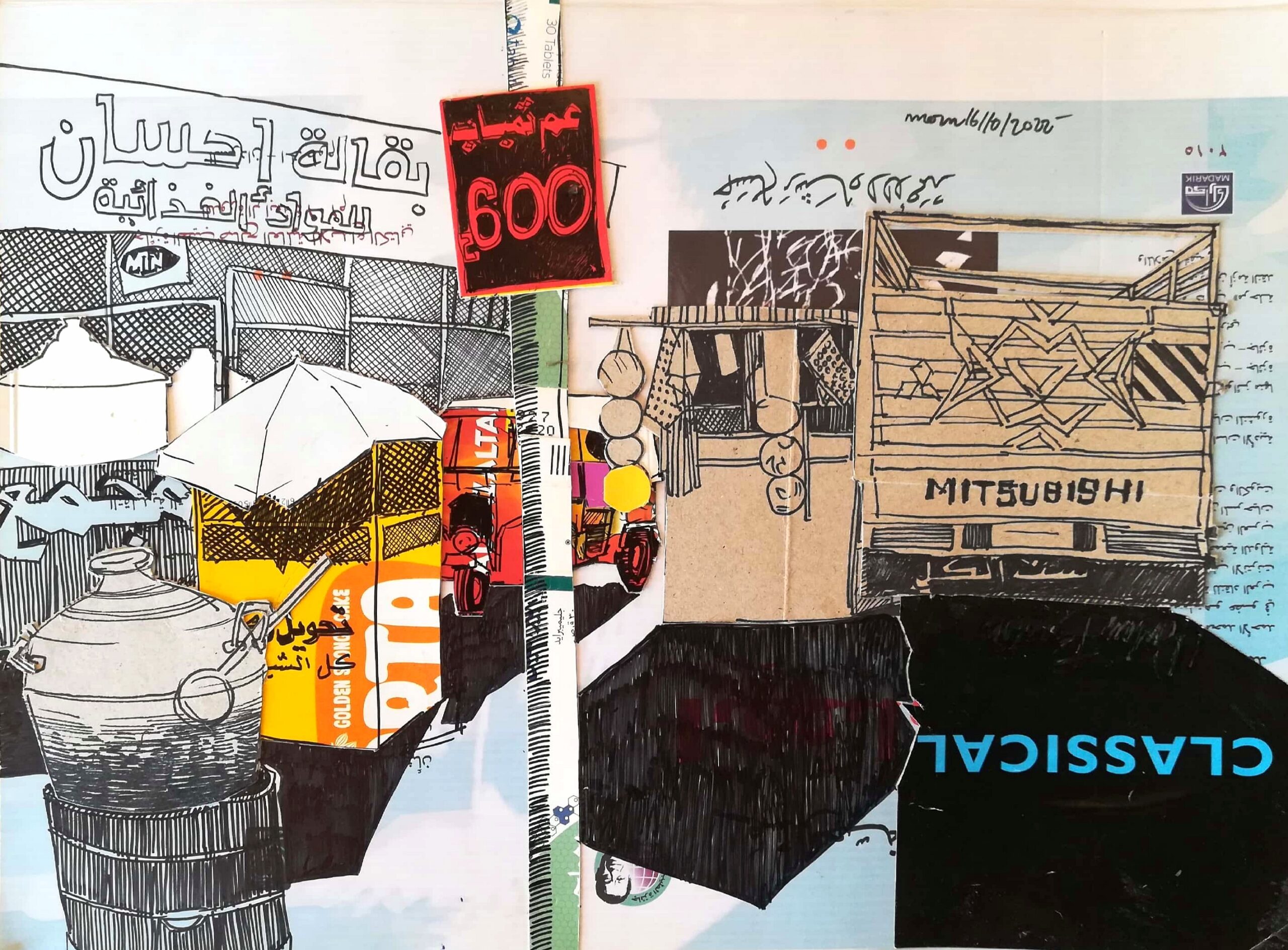

“A city whose humanity appears at airports when it farewells its people flying away to distant countries, and at the funerals of its martyrs, carried to their graves while reacting with their photos on Facebook. It commemorates those who offered their lives generously on the streets and alleyways as a physical presence of absence. Its wise quotes are written on the backs of cars on dirt roads; comfort is sought in “tobacco” centres and “female tea-makers” in crowded, narrow alleyways full of trash, wet, smelly roads, voices, fumes of cars, cooked slowly by the heat of its sun, and curious people staring at fat women walking around..”

Mozafar Ramadan

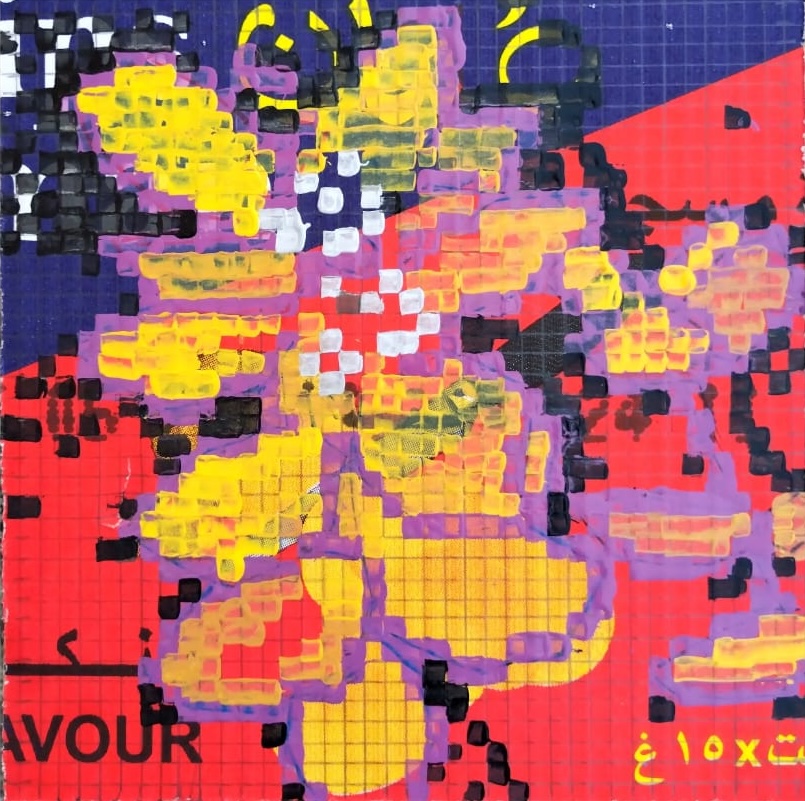

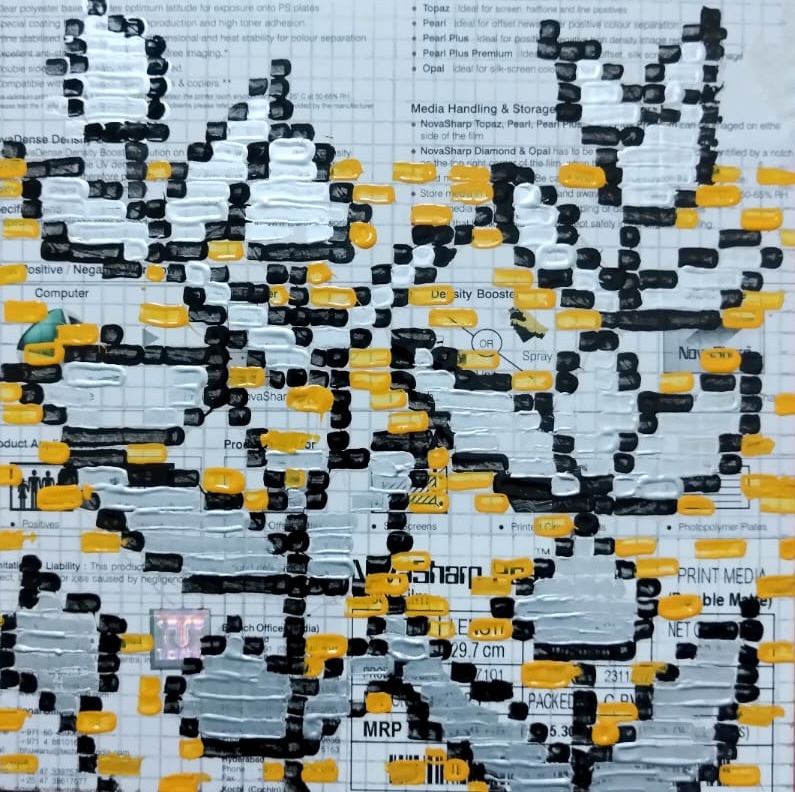

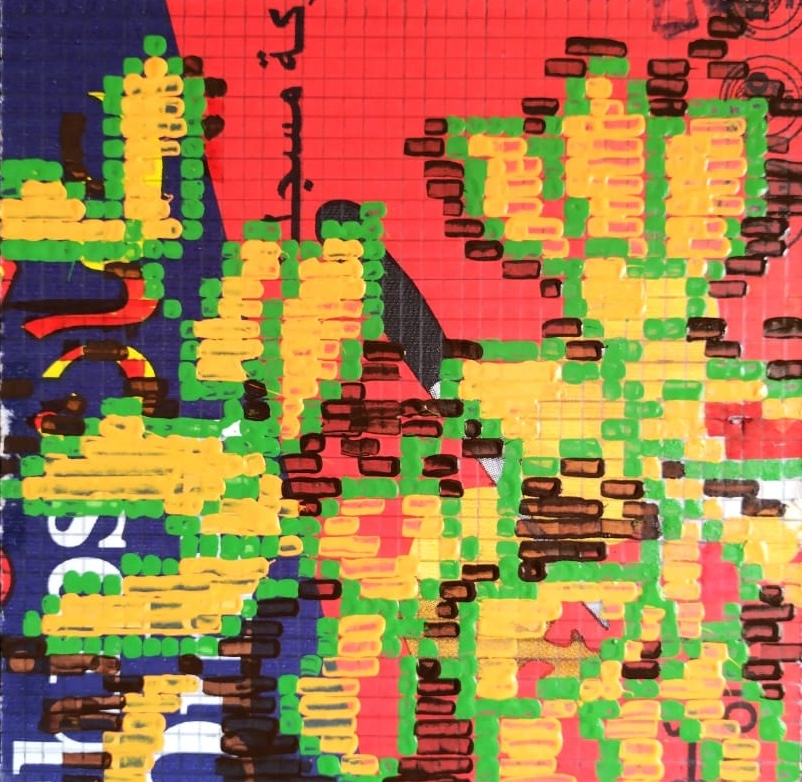

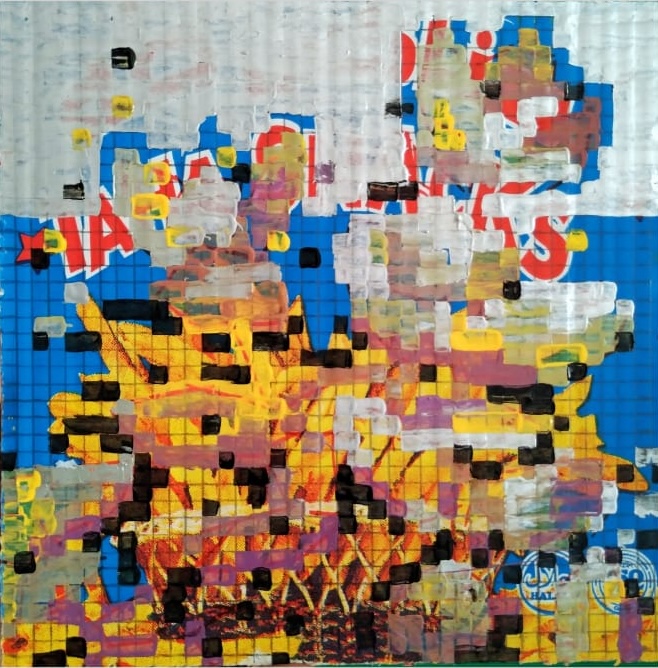

With these words, Mozafar Ramadan describes his city, Khartoum, painting a scene very familiar to the city’s nature and everyday life. He vividly illustrated this narrative in the dense, collaged compositions of his earlier artworks in Khartoum, pulsating with layered elements from the fruit vendors, street signs, textual fragments, and the clashing vibrancy of its public life. Accumulating the chaos and many elements and paradoxes that can be seen in the city’s busy fabric into compositions that reflect this rapidly changing yet familiar scene. But what happens to this visual image when we take the artist outside of his environment and place him in a temporary one? Which elements are lost from his memory, and which ones prevail in the foreground?

Through taking a closer look at Mozafar’s work on the semiotics of space, I focus on liminability and pose key questions to navigate “Temporality”: How do artistic forms capture the simultaneity of motion and stasis? What strategies emerge when the “temporary” becomes indefinite? Can alternative temporalities foster new modes of connection?

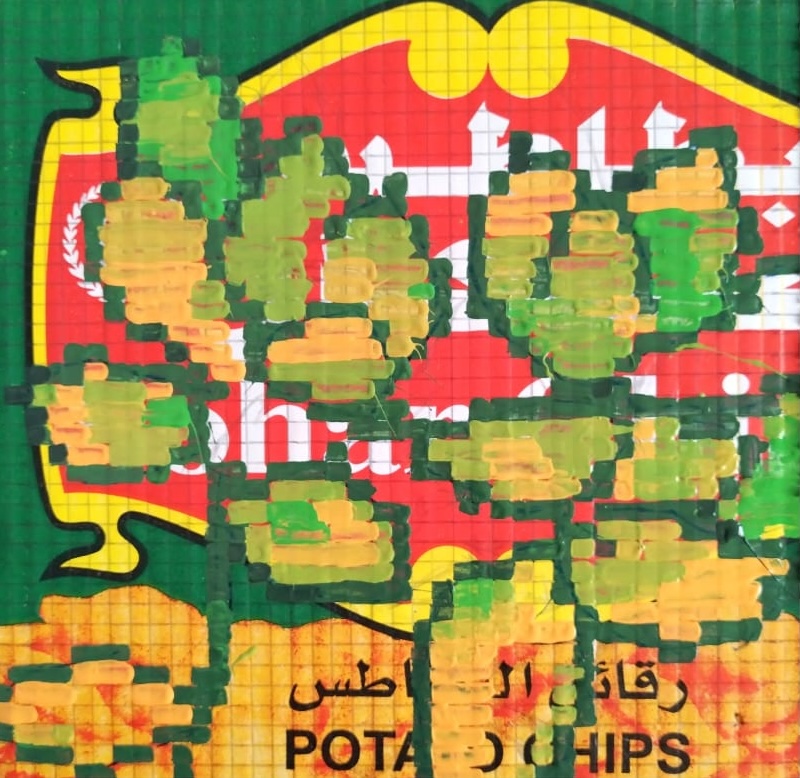

I follow Mozafar’s journey to Muscat, Oman, where he currently resides, and specifically look into his collection “Temporary – 2025,” a series of small-sized artworks that centre the “Al-Aushar” plant – scientifically known as Calotropis Procera, a commonly found plant in Sudan and the Sahara that grows randomly in deserted areas. “Al-Aushar” is a great paradox as a creature, as it is poisonous, yet is used medically to cure many diseases in local communities. It is believed that this plant is ominous and a sign of desertification and can cause blindness. In some folktales, it is even seen as a carrier of demons.

I see the existence of the plant as a constant that changes. In its persistence to survive, be of use, and then later on its death as an outsider to the environment, it embodies that state of “temporality” in action. I recall the many appearances of “Al-Aushar” around our neighbourhood in Khartoum, constantly being warned against as children, yet it kept growing and dying and growing again as we grew in age. Mozafar’s interest in the plant can be traced to his employment of its symbol as a prominent visual element of the temporality of our hometown. Although the plant prevails in harsh, deserted environments and is often found alone with no other trees of any kind around it, it is fragile. It grows rapidly to a certain height while the wind plays with its seeds, spreading them all around. It reaches this height and is then disposed of as it is no longer of use. This cycle is repeated over and over, and the artist here mirrors that in the construction and deconstruction of both his city and his being. In his self-imposed yet isolating exile in Muscat, he feels as if he is also an “Al-Aushar” plant, growing randomly in a desert as the wind plays with him and scatters his parts away from his family and what he has once known. Alone, looking odd in the place, no one around, and waiting for his roots to be cut off as he dreams of leaving the temporality of his exile.

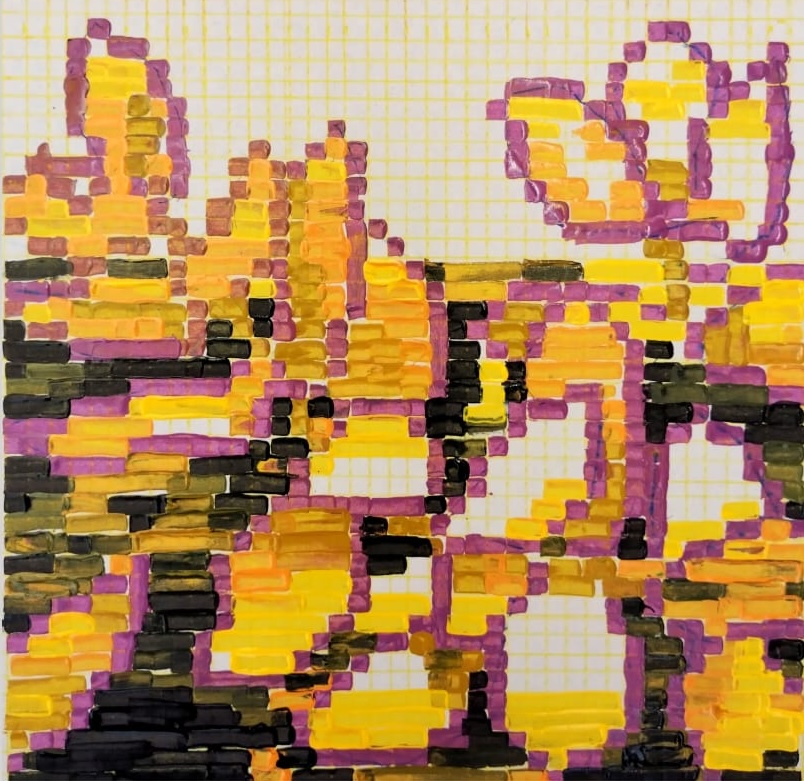

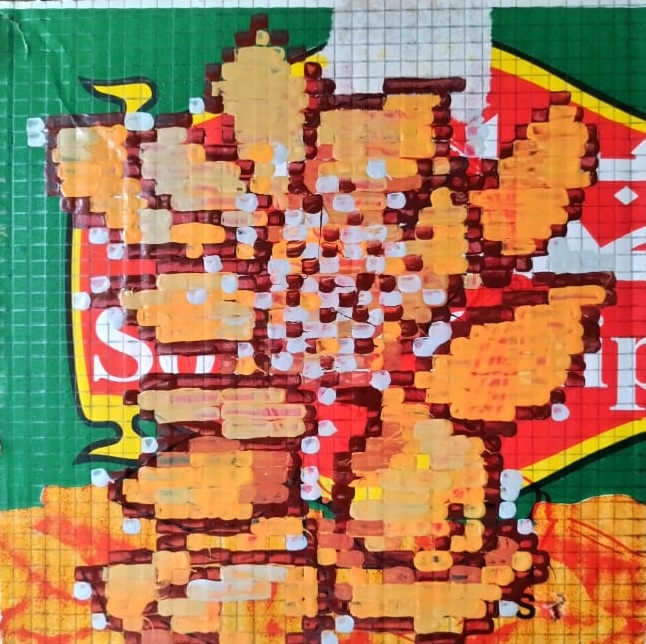

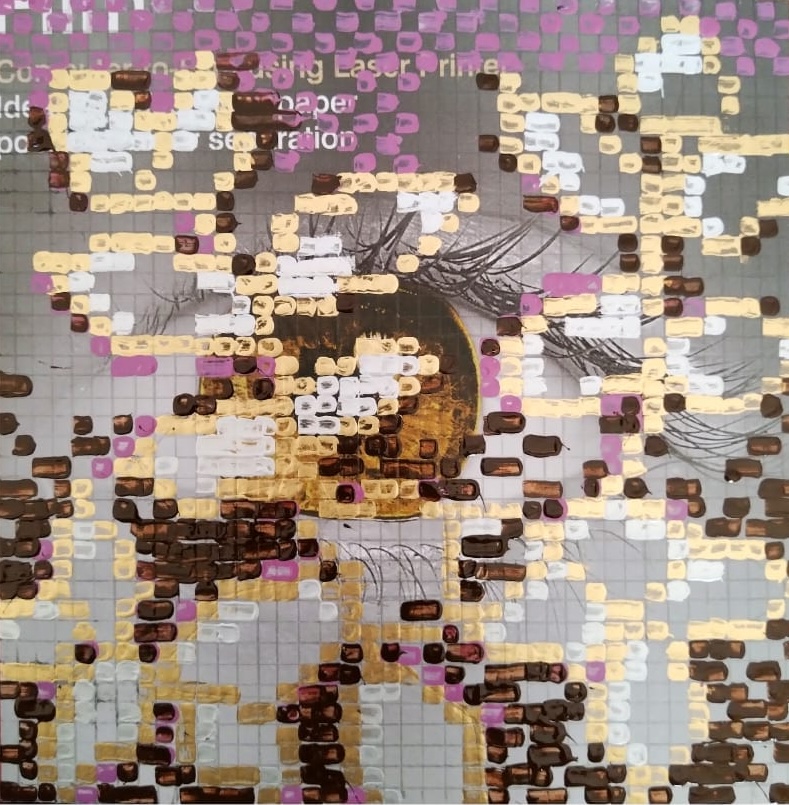

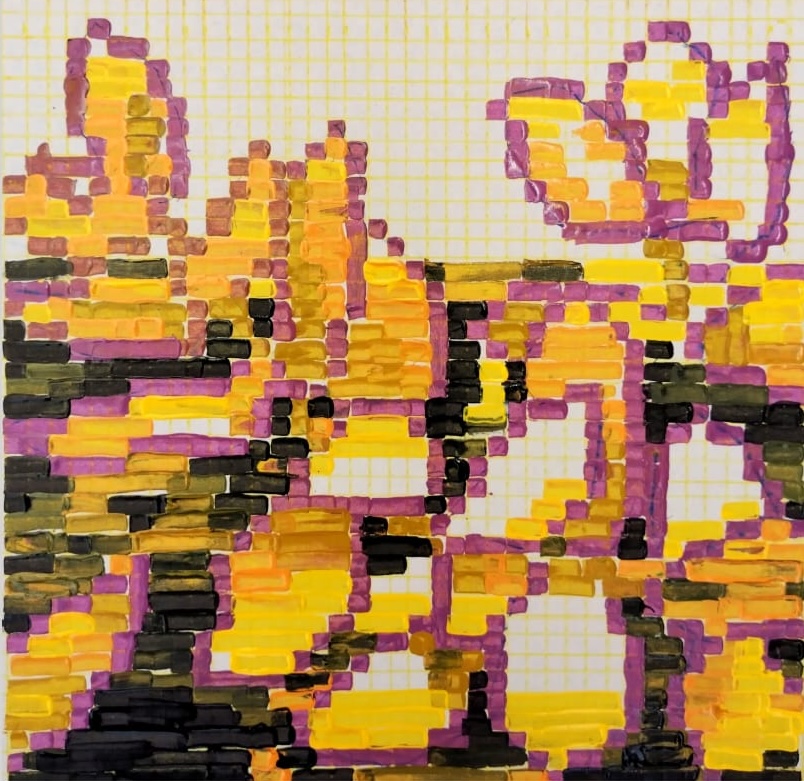

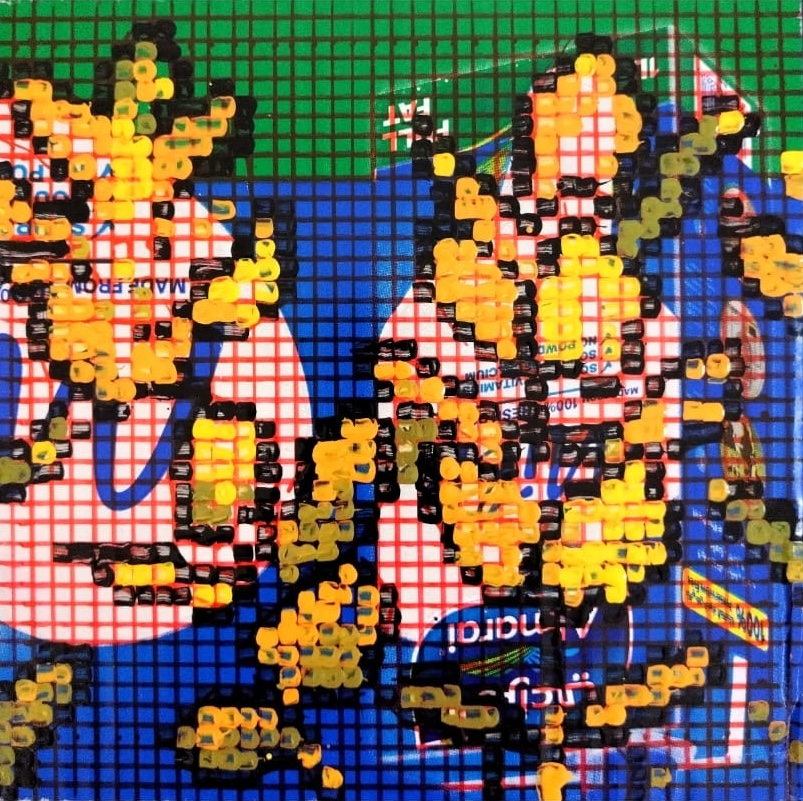

Ramadan’s layered work in his recent collection “Temporary” utilises recycled materials gathered from trash and disposed cardboard and ink from the printing workshop where he works. Visually, these manifest as delicate, repetitive tracings of the Al-Aushar’s form on weathered surfaces, ghostly patterns that emerge and dissolve between lines. His embodiment of the temporality state of the plant and its paradoxes is emphasised in his application of its pattern in repetition. He mimics the plant’s adaptability to its surrounding harsh environment using discarded materials to create, in relation to his own tactics of survival in Muscat.

The artist here employs abstraction to map psychic spaces and imagery shaped by waiting and uncertainty. His compositions build on the illusion of a familiar image smudged with distortion as it decays in the mind. His work rejects catastrophic temporality, instead proposing alternative rhythms that defy collapse.

The collection “Temporary” eradicates the chaos of the artist’s previous works and instead focuses on the loneliness and individuality of expatriation. This visual shift in his compositions mirrors the erosion of familiar structures – political, economic, and social – and the psychological recalibration required to navigate instability. By stripping away context to focus on the lone, paradoxical “Al-Aushur”, Mozafar asks how identity persists when external markers dissolve.

In one of the poems of Yemeni local poet Hussien Abubakr, he says,

Engraving on metal works and on stone,

Engraving does not hold on the stick of “Al-Aushar”,

النقش في الساج يصلح والحجر… ما يصلح النقش في عود العُشَر

This verse mirrors Mozafar’s own struggle: how does one etch permanence into a transience? Metal and stone hold memory, but Al-Aushar’s brittle stem rejects it. His exile, like the plant, persists yet evades fixation, rooted but resisting history. His artworks embody impermanence with recycled materials, smudged ink, and decaying cardboard, all refusing the illusion of fixity. If Khartoum was a city of chaotic inscriptions (on cars, walls, and Facebook tributes), then exile is the unmarked stick of Al-Aushar, a surface that erases as quickly as it forms. Mozafar’s work does not lament this fragility; instead, it asks, What grows in the absence of permanence? And what survives when even the engraving fades?